A Harvest of Hope for Veterans

by Adam Burke

Guidepost

I joined the Army to get away from the farm. Little did I know it would save me when I came home.

The guy in the mall food court was hard to miss. It wasn’t just his threadbare clothes and duffel bag. It was the way he scanned the tables, more focused on the food than the people. When my wife, Michele, and I stood and picked up our trays, he came over. “If you’re not going to finish that sandwich, I’ll take it,” he said.

“Sure,” I said, disturbed that a young guy—no more than 25—had to ask strangers for leftovers. Then something on his duffel caught my eye. A military ID patch. He was a homeless vet, back from combat with no idea where to go.

That could have been me.

I grew up in Webster, Florida, on my parents’ blueberry farm. I couldn’t wait to escape small-town life. The Army was my ticket out. See the world and serve my country...what could be a better adventure? I enlisted just out of high school.

By the time my unit deployed to Iraq in 2003, I was 26, a sergeant, newly married to a beautiful pediatric nurse. I was excited about seeing action. Michele wasn’t. “Before, you were on support missions. This is combat. I’m scared.”

“Try not to worry,” I said. “I’ll be fine.”

My first months in Iraq were more of a grind than dangerous. Then my platoon started running missions in the densely populated, tumultuous Sunni Triangle. We had to be on constant high alert. You never knew who the enemy was (they weren’t in uniform) or where they might be holed up. Your nerves never rested.

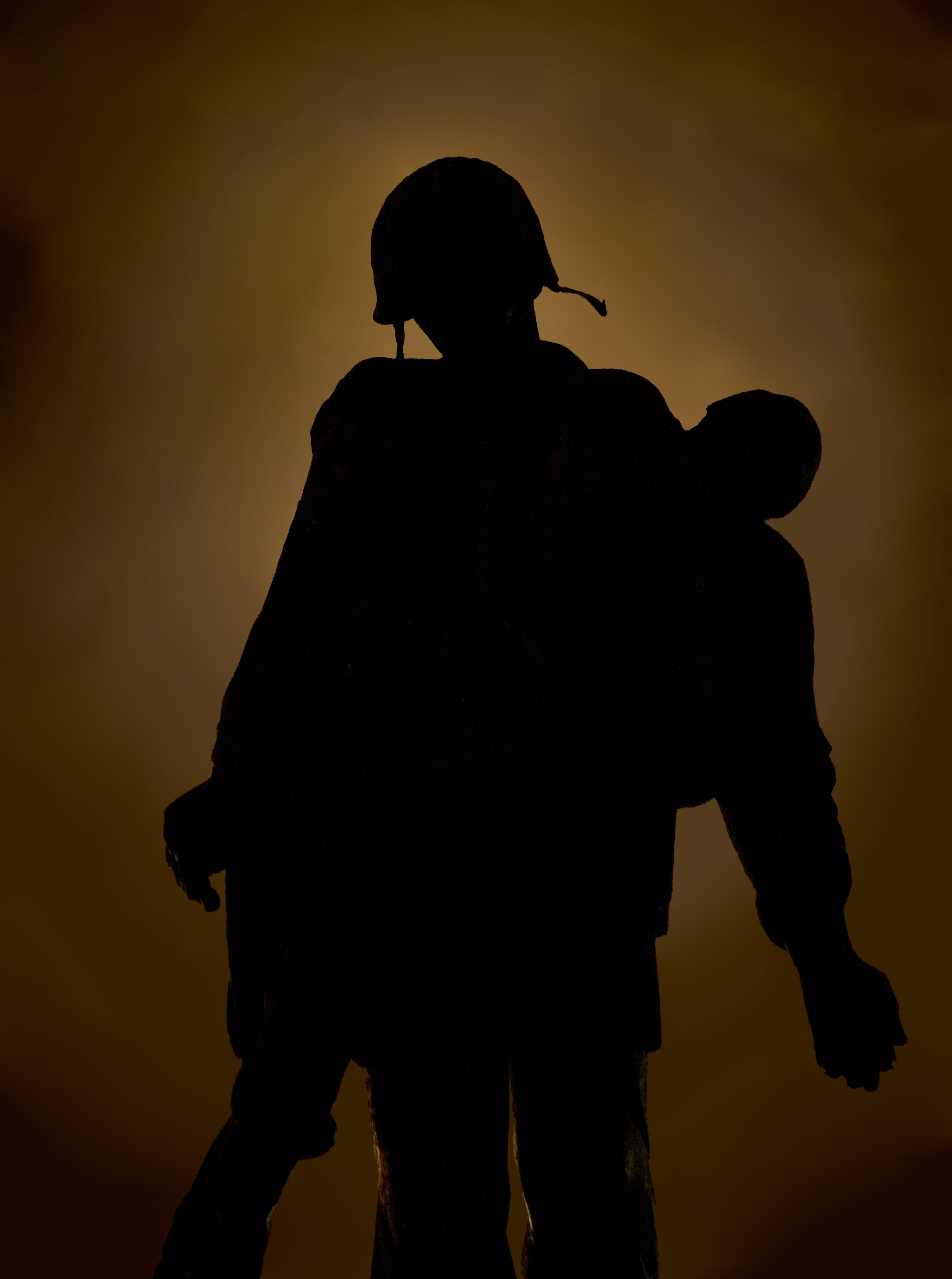

In May 2004, two weeks before my tour of duty was due to end, we were clearing a village said to be an insurgent stronghold. One of my guys went down, hit by a sniper. I ran out to pull him to cover. A mortar bomb knocked me off my feet. Shrapnel ripped into my legs and head.

I lay in the dirt, helpless, bombs exploding around me, my men returning fire. All I could think of was Michele, my family and how desperately I wanted to see them again. Lord, can you see me? If you get me home, I promise I’ll make my life worth saving. Then I passed out.

I came to in a military hospital in Iraq. Surgeons couldn’t remove all the shrapnel. Back in the States, I was in and out of hospitals for months. The diagnosis: traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

I had blinding headaches, memory and other cognitive problems and balance issues so I needed a cane to walk. My military career was done.

The hyper-vigilance that kept me alive in the war zone didn’t translate well to civilian life. My anxiety was intense. Being around even a few people made me jittery. I woke up sweat-drenched from nightmares. It seemed like everything I used to count on—strength, discipline, toughness—had been stripped away.

Except for Michele and her love for me, her patience. She encouraged me to go back to school. It was slow going because of my TBI-related cognitive impairments, but I got a business degree. I found work with a healthcare-staffing firm.

It didn’t take long to see an office job wasn’t for me. I was still riddled with anxiety. Sometimes I’d think about that promise I’d made to the Lord lying in the street in Iraq. Would I ever be able to make good on it? Would it have been better if I had not made it back? No, no, I couldn’t think like that!

When my family offered me a small plot of land on the old farm in Webster, my first instinct was to say no. The tedium, the isolation, the labor in the fields...hadn’t I spent all these years trying to get away from the farm? Michele convinced me to give it a try. “Farming’s in your blood,” she said. “Maybe this is what you need.”

I decided to go with what I knew best—blueberries. Researching organic farming methods, figuring out the right plants and soil mix, got my brain in gear like nothing else. A great group called the Farmer-Veteran Coalition helped me buy my first bushes. I used my disability pay to get an irrigation system.

Then came the morning I went out onto my little patch of land to start planting. I got down on my knees, dug my hands into the dirt. The earthy smell of it brought a rush of memories. When I was little I used to love plunging deep into the rows of bushes where no one could see me.

It was like being in my own blueberry forest, so beautiful and peaceful it was almost holy. There’s no hurry here, I thought. The only sound was birds chirping. No noise, no pressure, no worries. Maybe for the first time since I’d been wounded, my heart and mind stopped racing. That calm didn’t leave me all day. Finally I stood and surveyed the neat rows of blueberry bushes I’d planted. Tiring work, but so satisfying to have something to show for it.

Michele helped during her off hours, but mostly I worked the field alone. One by one other veterans started to come out and join us. Then they brought along other vet buddies. We had different post-combat issues, but they all seemed to work themselves out on the farm.

My coordination and balance improved and I got rid of my cane. My thinking and memory sharpened, my anxiety subsided. Working together helped us feel comfortable around other people again.

Even the crowds at the mall no longer fazed me, which was why I was there that day when the young homeless vet asked for leftovers. All the way home, I couldn’t get him out of my mind. “I wish I knew how to help guys like him,” I told Michele. “More than a handout...”

“You’ll find a way,” she said.

“If only he could work on a farm like ours,” I said, “he’d get back on track.”

That’s when it came to me. What if I expanded our farm and made it a place where disabled veterans could work and heal and reintegrate into civilian life? I made tons of phone calls trying to find a way to turn my idea into reality.

Someone put me in touch with Work Vessels for Veterans, a group that gives returning vets start-up tools for new careers. In my case, that was eight acres of farmland near Jacksonville, where there are large numbers of returning military.

Things took off from there. Veterans Farm is thriving. There’s a fellowship program so disabled vets can earn a living while they learn to run an organic farm. At the end, they get seed money to start their own farms. We grow fruit and vegetables, raise tilapia and chickens and keep bees.

Our biggest crop is blueberries. We sell them at farmers markets as Red, White and Blueberries.

That young man from the mall? I never saw him again. I pray he finds his way. He helped me find mine. And if he ever needs work, I know a farm that can use his help, a place of promise fulfilled under the loving eye of the Lord.

2 Corinthians 4:16

Jeremiah 29:11

Credit: Guidepost